“Parasocial” is the term for one-sided relationships of the

sort we might have with celebrities: we know them (to some extent) but they

don’t know us at all. These one-sided relationships existed even in ancient

times when the only media were handwritten scrolls, statues, and word-of-mouth

rumors about the elite and famous, but they got an enormous boost with the

arrival in the 20th century of movies and recordings that seem to

bring us face to face or within earshot. Fans are known to become emotionally

attached to these well-known strangers enough to experience genuine grief when

they die. The phenomenon was examined back in 1985 by Richard Schickel in Intimate Strangers: The Culture of Celebrity

in America, a book that now seems rather quaint in today’s age of virtual

interactions on online social media where twitter posts can masquerade as actual

conversations. Most of us understand the limitations of parasocial

relationships. Those who don’t understand them form the pool from whom stalkers

emerge.

|

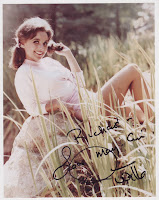

| Dawn Wells (1938-2020) "Mary Ann" |

A more curious phenomenon, also regarded as parasociality, is a relationship with fictional characters. This, too, has ancient precedents. Long before Homer’s epics were written down around 700 BCE (prior to which they were an oral tradition) people sat around the hearth fires and listened to bards recite stories of Troy and tales of brave Ulysses. The listeners surely felt they knew the characters as well as they knew their own neighbors. Again, modern media make the illusion all the more convincing. In the 1960s there was a common debate among high school boys of Mary Ann vs. Ginger on the TV show Gilligan’s Island. Being a smart-aleck teenager at the time, I tended to respond dismissively: “Like, you know they’re fictional, right?” But in truth I knew exactly why the debaters debated, and had an unvoiced opinion. Beyond the superficial level of schoolboy crushes, people often become deeply invested in their favorite shows. They care about the characters and what happens to them. On some level viewers regard the characters on Friends as friends. The prevailing opinion among psychologists is that up to a certain point this is perfectly healthy: a normal expression of empathy. Below the most surface level of consciousness our minds aren’t good at distinguishing between fictional characters and real ones – assuming the scriptwriters and actors are halfway competent. Dr. Danielle Forshee on her website says “your brain recognizes the human emotion they are portraying and starts to feel connected to those characters.” Also, the characters can be avatars of ourselves, and so it can be cathartic and helpful to see them work through difficulties we’ve faced ourselves. It can be disturbing to watch them get into avoidable trouble (by marrying the obviously wrong person, for example) just as it is disturbing to watch a real friend do it – or, worse, do it ourselves.

This is also why fans get so upset when book series or TV

shows don’t end the “right” way. Many shows get canceled abruptly and so have

no proper endings at all. (It’s a bit like being ghosted in real life.) This

frustrates fans but apparently not as much as deliberately crafted endings that

they don’t like. Google something like “beloved TV shows with hated finales”

and you’ll get a long list including Game

of Thrones, Dexter, Lost, Enterprise, Seinfeld, The Sopranos, and How I Met

Your Mother, among many others. Sometimes the finales are truly slapdash

and unsatisfying, but even well-crafted ones can annoy fans.

I actually like one of the most hated finales of all time: How I Met Your Mother. *Spoilers*

follow, so in the unlikely event the reader hasn’t ever seen the show, skip

this next part. The majority of fans are upset because 1) there isn’t a

“happily ever after” ending and 2) Ted reconnects with Robin after nine seasons

of the audience being told that they weren’t right for each other. Well, life

doesn’t have “happily ever after” endings. Mark Twain commented that love

affairs end either badly or tragically, and the tragic ending in HIMYM is the

way things go – earlier in this case than one might hope but frequent enough at

that age even so. Secondly, Robin and Ted weren’t

right for each other when Ted was looking for “the One” with whom to build a

home and family while Robin wanted a childless globetrotting career. Years

later, however, Ted is a widower father of grown children and Robin is successful

at her job and divorced. Their goals no longer clash but they still have a long

shared personal history. They might get on just fine. Times and circumstances

have changed. That doesn’t diminish Ted and Tracy; they were right for the kind

of life they had at the time they had it. (Besides, the point is often missed

that Ted is Tracy’s second pick; in one episode she talks to her deceased

partner whom she had regarded as “the One” about moving on.) Maybe my response is a matter of

age: I’m looking at things from the perspective of old done-that Ted, not young

aspirational Ted, but to me the ending makes perfect sense.

That I gave this matter any thought at all is a prime example

of parasociality. So, anyone at whom I snickered in high school for debating

Mary Ann vs. Ginger is fully within his rights to say to me about the

characters in HIMYM, “Like, you know they’re fictional, right?”

Cream

– Tales of Brave Ulysses

The monthly comic books with loved characters like Capt. America, the Avengers, Thor, etc. can be the same way. They can annoy fans if they go in certain directions, and people that love fandom talk about them as if they are real. Ha. One of the biggest debated franchises is the Star Trek universe and fans bicker back and forth over one thing or the other. I don't understand why Hollywood doesn't try and make something more akin to the original series (or some other network and call it another space opera title). Surely the formula wouldn't be that hard to replicate. I say that, being a fan. :)

ReplyDeleteThere is even an early precedent: the Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers franchises in the 1930s. Not only were the sets and tone similar, but Buster Crabbe played both characters.

Delete