Back in the 60s Lorne Greene had a singing career. Yes, I mean the actor who played the Cartwright patriarch on Bonanza and Commander Adama in the in the 1979 version of Battlestar Galactica. He even had a hit single (Ringo) in 1964. He didn’t really sing. He simply spoke lyrics in that bass voice of his, so his albums (six of them!) are really in the nature of poetry readings. He wasn’t afraid of unmitigated corn, and if you aren’t either you may want to sample a track or two. Or not. Anyway, in the late 60s or early 70s he appeared on some variety show. I no longer remember which one: imdb offers several possibilities and a quick search of youtube fails to turn up this particular clip. I do remember the recitation he gave, however, because of the opening line. He began, "They say a man needs three things to make his life complete: one good dog, one good horse, and one good woman." In that order?

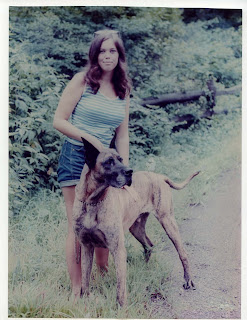

Well, I covered the horse a couple posts ago. The dog was a Great Dane named Woody. We were pups together, which makes a bond that can’t be repeated. He wasn’t mine alone. He was the family dog, but that made him all the more a part of my life at that time. Though Woody did come inside, he was too big and rambunctious really to be a house dog, so he spent the night in a dog house my dad built for him. The dog house was as big as a garden shed, had electric heat, and opened to an oversize dog run. Woody lived for 13 years, which is long for a big dog. My sister Sharon (1950-95) was the poet of the family, so I let her say the rest. She wrote this at age 16 or so. It’s right up Lorne Greene’s alley.

My dog runs after

the sticks I throw him.

Huge,

black-striped and muscled,

he has a mournful face.

Alone in the sun

I daydream of loves

and lavish my loving overflow

on my dog, hugging him.

He asks for nothing but sticks and loving

and does not complain

when locked up for the night.

– Sharon Bellush

Thursday, April 28, 2011

Sunday, April 24, 2011

Wilde Thing

From an Economist article: "Americans expect a lot from marriage. Whereas most Italians say the main purpose of marriage is to have children, 70% of Americans think it is something else. They want their spouse to make them happy. Some go further and assume that if they are not happy, it must be because they picked the wrong person."

Well, we’ve never been afraid of unrealistic expectations on this continent, but in this case (and perhaps a few others) maybe we should be. Another person cannot make you happy – at least not for very long. Most often we’re talking minutes. On the other hand, another person can make you miserable – and this time we’re talking years.

In my observation, people divide into two basic types: 1) Type Ones are happy by default, which is to say they are just naturally happy unless bad things are happening to them; 2) Type Twos are just the opposite: they are naturally unhappy unless good things are happening to them, and they default back to unhappiness whenever the good things stop. If your default state is “happy,” you don't need anyone to cheer you up; you might like it now and then, but you don’t need it. You’ll be just fine whittling on the porch by yourself, and much of the time you prefer it. If your default state is “unhappy,” no one person ever will supply you with enough good things to keep you smiling; you’ll always need to seek out more fun and excitement to break the gloom. Type Ones are rarely ambitious; they think things are just fine so long as there is food to eat, a couch to sit on, and no one bothering them. Type Twos are chronically antsy, dissatisfied, and impatient, but for those very reasons are better motivated to accomplish more.

Type Ones and Type Twos drive each other crazy. They nearly always marry each other.

Do I have any advice? Since my own marriage (yes, a Type One and Two) lasted scarcely more than three years, arguably I’m not well qualified to give any. I’ll give some anyway. After all, said Oscar Wilde, "I always give away good advice. It never is of the slightest use to myself." So, here goes. If you are determined not to be single, just aim for someone who doesn't make you miserable. At least he or she won't get in the way of whatever your default state is.

Well, we’ve never been afraid of unrealistic expectations on this continent, but in this case (and perhaps a few others) maybe we should be. Another person cannot make you happy – at least not for very long. Most often we’re talking minutes. On the other hand, another person can make you miserable – and this time we’re talking years.

In my observation, people divide into two basic types: 1) Type Ones are happy by default, which is to say they are just naturally happy unless bad things are happening to them; 2) Type Twos are just the opposite: they are naturally unhappy unless good things are happening to them, and they default back to unhappiness whenever the good things stop. If your default state is “happy,” you don't need anyone to cheer you up; you might like it now and then, but you don’t need it. You’ll be just fine whittling on the porch by yourself, and much of the time you prefer it. If your default state is “unhappy,” no one person ever will supply you with enough good things to keep you smiling; you’ll always need to seek out more fun and excitement to break the gloom. Type Ones are rarely ambitious; they think things are just fine so long as there is food to eat, a couch to sit on, and no one bothering them. Type Twos are chronically antsy, dissatisfied, and impatient, but for those very reasons are better motivated to accomplish more.

Type Ones and Type Twos drive each other crazy. They nearly always marry each other.

Do I have any advice? Since my own marriage (yes, a Type One and Two) lasted scarcely more than three years, arguably I’m not well qualified to give any. I’ll give some anyway. After all, said Oscar Wilde, "I always give away good advice. It never is of the slightest use to myself." So, here goes. If you are determined not to be single, just aim for someone who doesn't make you miserable. At least he or she won't get in the way of whatever your default state is.

Wednesday, April 20, 2011

Sunny Days

Seasonable weather has arrived for hitting the trails again – on horseback, that is. In my intrepid youth, without the excuse of a postal route, “neither snow, nor rain, nor heat, nor gloom of night” deterred me from riding throughout the year, but nowadays I like to be dry, warm, and able to see where I’m going.

I’ve been a rider since I was 11, which was rather a late start, if most of my riding companions are to be believed. I’ve kept up with riding ever since, yet in all those years I’ve owned only one horse of my own, and him only briefly. It is and always has been much easier and vastly cheaper to rent by the hour. Few people outside of NJ think of the state as horse country, yet it is. The US Equestrian Team is HQ’d here. There are lots of stables, facilities, and trails, so finding a place to ride is not a problem. While I was (also briefly) married, “we” owned as many as six horses at one point, it is true, but five of those most emphatically were hers. It has been a decade since I last saw the one who was mine, but I owe him a mention beyond the thinly disguised depiction in one of my short stories – especially since my current re-edit of that story has snipped him out of it. (That’s his fictional alter ego in the old cover pic below.)

I first laid eyes on Sunny in 1999. At the time, my wife Sandy already owned two pleasure horses, but she believed she could make money by buying unschooled horses, training them for the show circuit, and then selling them at a profit. (She later liked to wear a T-shirt that read, “I made a small fortune in horses. I started with a large fortune.” The initial fortune was not, in fact, large, but as an expression of a trend, the shirt was accurate.) She had childhood connections with horse farmers in Virginia and North Carolina, so that’s where she made up her mind to search. Not being a terribly patient sort, she then made one of her incomparable decisions: she insisted on driving directly into Hurricane Floyd, which at that moment was battering Virginia Beach. No exhortations to wait a week availed. She would go on her own, she said, if I didn’t accompany her, so we went.

Sandy found the 6-year-old 16 hand palomino Sunny in a barn with only half a roof. The hurricane had removed the other half. She acquired one more horse on that trip and two more horses afterward, but Sandy soon suggested I keep Sunny, instead of putting him up for resale. In part this was because she felt I should have a horse of my own, but mostly it was because I was the only one who could handle him on the ground. Sunny liked me. That meant he didn’t actually try to kill me. He still would bite, cow kick, and shoulder me up against the wall of a stall, but at least he would allow me to get tack and blankets on and off him. He wasn’t so polite to anyone else.

Though his ground manners were bad, he was competent in the ring. More importantly from my perspective, since my last entry in a horse show was in 1967 and I planned no future one, he was a superb trail horse. He always went where he was pointed, which not all horses do. Some are afraid of water, some don’t like the woods, some won’t cross bridges, some won’t walk past a dog, and so on. Sunny didn’t care, and he never spooked. Sometimes he got angry, but he never spooked. Once on a park trail, for example, a bicycle rider silently approached from behind and whizzed past us at high speed. Sunny wasn’t afraid, but it was all I could do to keep his business end turned away from the trail, because by then he had his eyes on the cyclist’s companion following some 20 yards behind. With his ears laid back, Sunny plainly intended to take him out. I managed to prevent it, though after the second cyclist passed, Sunny let out a kick at nothing in particular, just to express a point, I suppose.

Sunny’s ground habits improved slowly over time, though they never became good. It eventually became possible for someone other than myself to tack him. One of Sandy’s advanced adult riding students took a liking to him and she didn’t fear him on the ground. Keeping multiple horses was crushingly expensive for us, so I agreed to sell him. The new owner, for financial reasons, also decided to sell him about a year later, and I lost track of him at that point. (More attention-consuming events intervened, including divorce and deaths in the family.) I don’t know where he is today, but, if he is still alive, I’m sure he is cow-kicking, shoving, and bullying his owner, who puts up with it for the trouble-free rides.

I’ve been a rider since I was 11, which was rather a late start, if most of my riding companions are to be believed. I’ve kept up with riding ever since, yet in all those years I’ve owned only one horse of my own, and him only briefly. It is and always has been much easier and vastly cheaper to rent by the hour. Few people outside of NJ think of the state as horse country, yet it is. The US Equestrian Team is HQ’d here. There are lots of stables, facilities, and trails, so finding a place to ride is not a problem. While I was (also briefly) married, “we” owned as many as six horses at one point, it is true, but five of those most emphatically were hers. It has been a decade since I last saw the one who was mine, but I owe him a mention beyond the thinly disguised depiction in one of my short stories – especially since my current re-edit of that story has snipped him out of it. (That’s his fictional alter ego in the old cover pic below.)

I first laid eyes on Sunny in 1999. At the time, my wife Sandy already owned two pleasure horses, but she believed she could make money by buying unschooled horses, training them for the show circuit, and then selling them at a profit. (She later liked to wear a T-shirt that read, “I made a small fortune in horses. I started with a large fortune.” The initial fortune was not, in fact, large, but as an expression of a trend, the shirt was accurate.) She had childhood connections with horse farmers in Virginia and North Carolina, so that’s where she made up her mind to search. Not being a terribly patient sort, she then made one of her incomparable decisions: she insisted on driving directly into Hurricane Floyd, which at that moment was battering Virginia Beach. No exhortations to wait a week availed. She would go on her own, she said, if I didn’t accompany her, so we went.

Sandy found the 6-year-old 16 hand palomino Sunny in a barn with only half a roof. The hurricane had removed the other half. She acquired one more horse on that trip and two more horses afterward, but Sandy soon suggested I keep Sunny, instead of putting him up for resale. In part this was because she felt I should have a horse of my own, but mostly it was because I was the only one who could handle him on the ground. Sunny liked me. That meant he didn’t actually try to kill me. He still would bite, cow kick, and shoulder me up against the wall of a stall, but at least he would allow me to get tack and blankets on and off him. He wasn’t so polite to anyone else.

Though his ground manners were bad, he was competent in the ring. More importantly from my perspective, since my last entry in a horse show was in 1967 and I planned no future one, he was a superb trail horse. He always went where he was pointed, which not all horses do. Some are afraid of water, some don’t like the woods, some won’t cross bridges, some won’t walk past a dog, and so on. Sunny didn’t care, and he never spooked. Sometimes he got angry, but he never spooked. Once on a park trail, for example, a bicycle rider silently approached from behind and whizzed past us at high speed. Sunny wasn’t afraid, but it was all I could do to keep his business end turned away from the trail, because by then he had his eyes on the cyclist’s companion following some 20 yards behind. With his ears laid back, Sunny plainly intended to take him out. I managed to prevent it, though after the second cyclist passed, Sunny let out a kick at nothing in particular, just to express a point, I suppose.

Sunny’s ground habits improved slowly over time, though they never became good. It eventually became possible for someone other than myself to tack him. One of Sandy’s advanced adult riding students took a liking to him and she didn’t fear him on the ground. Keeping multiple horses was crushingly expensive for us, so I agreed to sell him. The new owner, for financial reasons, also decided to sell him about a year later, and I lost track of him at that point. (More attention-consuming events intervened, including divorce and deaths in the family.) I don’t know where he is today, but, if he is still alive, I’m sure he is cow-kicking, shoving, and bullying his owner, who puts up with it for the trouble-free rides.

Sunday, April 17, 2011

Fat Chance

Waistlines are expanding in all wealthy countries, but this is one global race where the USA still is out in front. There is much handwringing (bellyaching?) about this among columnists and politicians. All ask “Why?” as though the answer were a mystery. There is no mystery. We eat too much.

There are a couple of myths that need correction as we seek out someone to blame. One is that restaurants generally impose larger portions on us than they did 50 years ago, and the other is that the foods we eat at home are less healthy now than they were then. Upper scale restaurants, it is true, do serve larger portions now, but Americans eat only a few percent of their annual calorie intake in these places; these cannot be blamed for our weight gain. As for less expensive everyday places, portions are NOT larger. I remember what diners (the preferred fast food venues of the day) were like 50 years ago. The gravy-soaked open-face hot roast beef sandwich (or whatever main dish you ordered) came with buttered toast, heaping sides of hash browns, grits, succotash, and fried…well… everything, followed by a hunk of baked-in-house apple pie with vanilla ice cream on top. After we left the diner we’d likely go to a movie where we ate a bucket of buttered popcorn. After that, we would stop by the local ice cream fountain. These fountains were everywhere – especially in drug stores. The soda jerk poured you a milk shake from a tall metal jar and left the jar with you for a second and third pour. Burger joints, hot dog stands, and pizza parlors abounded then, as now, though fewer belonged to national chains. Most (though not all) of the burgers were smaller than modern day Whoppers or Quarter Pounders, but (trust me on this one) for that very reason we ordered two – and extra fries. We ate fewer calories out only because we didn’t go out as often. We didn’t have the money.

As for food at home, our diet was not by modern notions healthy. Yes, we had our veggies, but we drowned in dairy products. My family had four quarts delivered daily by the milkman, which was pretty typical. I drank at least one of them by myself. Eggs were not just for breakfast but also topped meatloaf at dinner. Gravy was likely to be “red eye” (fat drippings from the frying pan).

A USDA study supports my recollections (see http://www.usda.gov/factbook/chapter2.pdf). The percentage of fat in Americans’ diet actually has declined since 1970. It was 40% then and 33% today. Dairy consumption has declined so much that, despite the fat dangers, the USDA suggests Americans should drink more milk for the calcium. Annual red meat consumption has dropped 16 pounds per person since the peak (129.5 pounds) in 1970. The number of eggs per person has dropped from 285 to 250 in the same time period (down from a whopping 374 in the 1950s).

So, why aren’t we skinnier? Because our total calorie intake per person keeps rising – by nearly 25% since 1970 according to the same USDA report. So, even though the percentage of fat in our diet is lower, in absolute terms we eat more fat than ever. We cut back on those “unhealthy” red meats by 16 pounds since 1970, but we increased our consumption of poultry by 31 pounds (by 46 pounds since the 1950s); in addition, we increased consumption of fish and shellfish by 3 pounds. We replaced all that milk with soft drinks, which are not exactly an improvement. Fruit and vegetable consumption is up more than 23% since the 1970s, which sounds like a good thing, but it adds to the total calorie intake. The result: we now are eating an average 2700 calories per day, which is 530 calories more than in 1970.

Perhaps our biggest problem is our very habit of blaming everyone but ourselves. We are food addicts – and we do not have the option of going (so to speak) cold turkey with food as we do with other abused substances. Addicts of any kind get better only when they take responsibility for their own excesses.

“Stop eating so much” is far easier said than done, as I know painfully well. We all would like to be trim while still eating whatever we like. In practice, though, life involves trade-offs. There are a few fortunate souls whose appetites balance their metabolisms precisely; for most of us, though, our choice is to be trim and hungry or overweight and full. Perhaps we should just accept that some people pick the latter option and not moralize to them about it so much. Will they live shorter unhealthier lives? Yes. They know that. Riding motorcycles shortens expectancy, too. Both are free choices. With ever increasing frequency, we hear demands that someone else (restaurants, the FDA, supermarkets, or whoever) save us from ourselves; abdication of self-responsibility in matters of self-indulgence is always a dubious path to success.

There are a couple of myths that need correction as we seek out someone to blame. One is that restaurants generally impose larger portions on us than they did 50 years ago, and the other is that the foods we eat at home are less healthy now than they were then. Upper scale restaurants, it is true, do serve larger portions now, but Americans eat only a few percent of their annual calorie intake in these places; these cannot be blamed for our weight gain. As for less expensive everyday places, portions are NOT larger. I remember what diners (the preferred fast food venues of the day) were like 50 years ago. The gravy-soaked open-face hot roast beef sandwich (or whatever main dish you ordered) came with buttered toast, heaping sides of hash browns, grits, succotash, and fried…well… everything, followed by a hunk of baked-in-house apple pie with vanilla ice cream on top. After we left the diner we’d likely go to a movie where we ate a bucket of buttered popcorn. After that, we would stop by the local ice cream fountain. These fountains were everywhere – especially in drug stores. The soda jerk poured you a milk shake from a tall metal jar and left the jar with you for a second and third pour. Burger joints, hot dog stands, and pizza parlors abounded then, as now, though fewer belonged to national chains. Most (though not all) of the burgers were smaller than modern day Whoppers or Quarter Pounders, but (trust me on this one) for that very reason we ordered two – and extra fries. We ate fewer calories out only because we didn’t go out as often. We didn’t have the money.

As for food at home, our diet was not by modern notions healthy. Yes, we had our veggies, but we drowned in dairy products. My family had four quarts delivered daily by the milkman, which was pretty typical. I drank at least one of them by myself. Eggs were not just for breakfast but also topped meatloaf at dinner. Gravy was likely to be “red eye” (fat drippings from the frying pan).

A USDA study supports my recollections (see http://www.usda.gov/factbook/chapter2.pdf). The percentage of fat in Americans’ diet actually has declined since 1970. It was 40% then and 33% today. Dairy consumption has declined so much that, despite the fat dangers, the USDA suggests Americans should drink more milk for the calcium. Annual red meat consumption has dropped 16 pounds per person since the peak (129.5 pounds) in 1970. The number of eggs per person has dropped from 285 to 250 in the same time period (down from a whopping 374 in the 1950s).

So, why aren’t we skinnier? Because our total calorie intake per person keeps rising – by nearly 25% since 1970 according to the same USDA report. So, even though the percentage of fat in our diet is lower, in absolute terms we eat more fat than ever. We cut back on those “unhealthy” red meats by 16 pounds since 1970, but we increased our consumption of poultry by 31 pounds (by 46 pounds since the 1950s); in addition, we increased consumption of fish and shellfish by 3 pounds. We replaced all that milk with soft drinks, which are not exactly an improvement. Fruit and vegetable consumption is up more than 23% since the 1970s, which sounds like a good thing, but it adds to the total calorie intake. The result: we now are eating an average 2700 calories per day, which is 530 calories more than in 1970.

Perhaps our biggest problem is our very habit of blaming everyone but ourselves. We are food addicts – and we do not have the option of going (so to speak) cold turkey with food as we do with other abused substances. Addicts of any kind get better only when they take responsibility for their own excesses.

“Stop eating so much” is far easier said than done, as I know painfully well. We all would like to be trim while still eating whatever we like. In practice, though, life involves trade-offs. There are a few fortunate souls whose appetites balance their metabolisms precisely; for most of us, though, our choice is to be trim and hungry or overweight and full. Perhaps we should just accept that some people pick the latter option and not moralize to them about it so much. Will they live shorter unhealthier lives? Yes. They know that. Riding motorcycles shortens expectancy, too. Both are free choices. With ever increasing frequency, we hear demands that someone else (restaurants, the FDA, supermarkets, or whoever) save us from ourselves; abdication of self-responsibility in matters of self-indulgence is always a dubious path to success.

Wednesday, April 13, 2011

Sandman

Insomnia rarely is much of a problem for me, but, like most folks, I have the occasional night when sleep hovers out of reach but just close enough that getting up and doing something else seems like a bad idea. Too much evening caffeine is usually the issue in my case, though frets and worries always contribute. Eventually the windows brighten, my cats (far more reliable than any alarm clock) demand breakfast, and I get up to face the morning in even more than my usual daze.

These sleepless episodes don’t worry me too much. I know slumber will arrive in its own good time. I learned this as long ago as 1974. That was when I clocked my personal record for continuous time awake – and with the aid of no stimulants stronger than coffee. On a Tuesday morning in that year, I was acutely aware of a deadline. Two research papers, one of 5000 words and the other 10,000, were due on Friday, one at 11 a.m. and the other at 1 p.m., for two history classes at George Washington University, located in downtown Washington, DC. Both papers still needed substantial work.

I spent the next 75 hours awake doing research (sans internet, in those benighted days), writing, editing, typing, and also attending other classes. I took breaks for snacks and meals but did not sleep a wink. At 10:40 a.m. on Friday morning, I finished typing the very last bibliography entry, quickly sealed each paper into its respective cover, and hurried out of my dorm. I still recall the sensations as I strolled along F Street. I didn’t actually feel sleepy. Sleepiness per se had departed 24 hours earlier. Instead, my vision was fuzzy, all the sounds of DC traffic were muted, and, as my feet trod the pavement, I could have sworn that big soft pillows were strapped to my shoes. Door handles felt as though they were made out of foam rubber, and it surprised me that they didn’t bend when I pulled on them. I remember how far away the voices of my professors sounded in classes that day, and how it didn’t occur to me to listen to what they actually were saying.

The papers were delivered on time. They were page-turners: The Impact of a Vulnerable Grain Supply on the Imperialism of Fifth Century Athens and A History of Land Use in the Township of Mendham from Colonial Times to 1974. Fear not, I have no plans to post either here. Though writing these did not put me to sleep, reading them must have been a soporific experience for my professors – assuming they did read them. Each paper received an A-, which leads me to suspect they didn’t; I wouldn’t have scored either so highly.

After class, I returned to my dorm room, which was about the size of a walk-in closet, but was at least roommate-free. The clock read 2:20. I dropped onto the bed. When I awoke the clock read 9:35. My first thought was, “I must have left the light on.” I didn’t. It was not, of course, 9:35 Friday night, but 9:35 Saturday morning. I had just set another personal record, this time for hours of continuous sleep.

I never tried to break either record since then, and don’t intend to do so in the future. I do know, however, that, sooner or later, sleep assuredly will come, and so will the morning.

Scene of the crime:

My dorm room at GW.

These sleepless episodes don’t worry me too much. I know slumber will arrive in its own good time. I learned this as long ago as 1974. That was when I clocked my personal record for continuous time awake – and with the aid of no stimulants stronger than coffee. On a Tuesday morning in that year, I was acutely aware of a deadline. Two research papers, one of 5000 words and the other 10,000, were due on Friday, one at 11 a.m. and the other at 1 p.m., for two history classes at George Washington University, located in downtown Washington, DC. Both papers still needed substantial work.

I spent the next 75 hours awake doing research (sans internet, in those benighted days), writing, editing, typing, and also attending other classes. I took breaks for snacks and meals but did not sleep a wink. At 10:40 a.m. on Friday morning, I finished typing the very last bibliography entry, quickly sealed each paper into its respective cover, and hurried out of my dorm. I still recall the sensations as I strolled along F Street. I didn’t actually feel sleepy. Sleepiness per se had departed 24 hours earlier. Instead, my vision was fuzzy, all the sounds of DC traffic were muted, and, as my feet trod the pavement, I could have sworn that big soft pillows were strapped to my shoes. Door handles felt as though they were made out of foam rubber, and it surprised me that they didn’t bend when I pulled on them. I remember how far away the voices of my professors sounded in classes that day, and how it didn’t occur to me to listen to what they actually were saying.

The papers were delivered on time. They were page-turners: The Impact of a Vulnerable Grain Supply on the Imperialism of Fifth Century Athens and A History of Land Use in the Township of Mendham from Colonial Times to 1974. Fear not, I have no plans to post either here. Though writing these did not put me to sleep, reading them must have been a soporific experience for my professors – assuming they did read them. Each paper received an A-, which leads me to suspect they didn’t; I wouldn’t have scored either so highly.

After class, I returned to my dorm room, which was about the size of a walk-in closet, but was at least roommate-free. The clock read 2:20. I dropped onto the bed. When I awoke the clock read 9:35. My first thought was, “I must have left the light on.” I didn’t. It was not, of course, 9:35 Friday night, but 9:35 Saturday morning. I had just set another personal record, this time for hours of continuous sleep.

I never tried to break either record since then, and don’t intend to do so in the future. I do know, however, that, sooner or later, sleep assuredly will come, and so will the morning.

Scene of the crime:

My dorm room at GW.

Sunday, April 10, 2011

Runaways

Back in the 70s I was aware of the existence of The Runaways and I had heard some of the group’s music, but I couldn’t have associated correctly one with the other. I simply didn’t pay the band any real attention. In the 80s, however, I did pay attention to (and like) Joan Jett and the Blackhearts. I still frequently play Joan’s Best of album, which is good, solid, un-frilled and unapologetic rock and roll. In the 70s Joan Jett had been the core of The Runaways, writing many of the songs for the earlier group. Lita Ford, who continues to record and tour successfully in 2011, was on guitar.

The Runaways were an all-girl power-rock band. I do mean “girl.” In 1975 all its members were minors, hence prompting the term “jailbait rock.” Joan was 16 and the lead singer Cherie Currie was 15. The Runaways owed much of their success to eccentric promoter/manager Kim Fowley; his job was made easier by the fact that the girls happened to be really good. The band’s career was portrayed in 2010 in the movie The Runaways. The film was based primarily on Neon Angel, the autobiography of Cherie Currie; Joan Jett is credited as an executive producer.

I caught the film in the theater last year and again on dvd last week. It’s not a future classic, and its story of premature fame leading to addiction and self-destruction is an all too familiar one. Nevertheless, it’s not bad, and, both as a cautionary tale and as a window to the 70s rock era, it is worth a look. Michael Shannon wonderfully plays Kim Fowley as a sort of bizarro version of R. Lee Ermey’s drill sergeant in Full Metal Jacket. Kristen Stewart and Dakota Fanning are entirely credible as Joan and Cherie. As is necessarily the case in a 106 minute film, the personal backgrounds of the bandmembers are drawn sketchily when at all, though we do see some of Currie’s unstable home life.

A friend with whom I watched the film in the theater commented at the time, “You know, our families were just way too functional.”

“Yes,” I agreed. “It ruined our careers.”

The bulk of the film shows the band’s early struggles followed by success, exploitation, sex, drugs, overwork, dissipation, dissolution, and uneven recovery.

Anyone interested in the fate of Cherie Currie after she quit the band should pick up Neon Angel, which is a good if disturbing read. Ever worsening drug abuse undermined her solo recording efforts and then destroyed an acting career in its early stages. Her association with drug dealers and users led to repeated hospitalizations and extreme victimizations. She woke up one day in the hospital with her heart and organs failing. The doctor told her if her addiction was untreated she would be “dead within weeks.” Cherie’s recovery began then.

Currie survived long enough to reach a point where recovery was possible for her. Many others are not so lucky. Why are some people so all-consumed by booze and drugs while others can use (even abuse) them without going into a death spiral? I don’t know, but in my experience (anecdotal though this may be), there is an observable risk factor. Anyone who cannot put everything aside for a while and just enjoy “being” is at especial peril. Some, like Cherie, eventually can find their way to this mellow place so that they can stand living without being intoxicated. Cherie Currie is currently a chain saw artist – really.

TV appearance of The Runaways in Japan: the actual group, not a scene from the movie.

The Runaways were an all-girl power-rock band. I do mean “girl.” In 1975 all its members were minors, hence prompting the term “jailbait rock.” Joan was 16 and the lead singer Cherie Currie was 15. The Runaways owed much of their success to eccentric promoter/manager Kim Fowley; his job was made easier by the fact that the girls happened to be really good. The band’s career was portrayed in 2010 in the movie The Runaways. The film was based primarily on Neon Angel, the autobiography of Cherie Currie; Joan Jett is credited as an executive producer.

I caught the film in the theater last year and again on dvd last week. It’s not a future classic, and its story of premature fame leading to addiction and self-destruction is an all too familiar one. Nevertheless, it’s not bad, and, both as a cautionary tale and as a window to the 70s rock era, it is worth a look. Michael Shannon wonderfully plays Kim Fowley as a sort of bizarro version of R. Lee Ermey’s drill sergeant in Full Metal Jacket. Kristen Stewart and Dakota Fanning are entirely credible as Joan and Cherie. As is necessarily the case in a 106 minute film, the personal backgrounds of the bandmembers are drawn sketchily when at all, though we do see some of Currie’s unstable home life.

A friend with whom I watched the film in the theater commented at the time, “You know, our families were just way too functional.”

“Yes,” I agreed. “It ruined our careers.”

The bulk of the film shows the band’s early struggles followed by success, exploitation, sex, drugs, overwork, dissipation, dissolution, and uneven recovery.

Anyone interested in the fate of Cherie Currie after she quit the band should pick up Neon Angel, which is a good if disturbing read. Ever worsening drug abuse undermined her solo recording efforts and then destroyed an acting career in its early stages. Her association with drug dealers and users led to repeated hospitalizations and extreme victimizations. She woke up one day in the hospital with her heart and organs failing. The doctor told her if her addiction was untreated she would be “dead within weeks.” Cherie’s recovery began then.

Currie survived long enough to reach a point where recovery was possible for her. Many others are not so lucky. Why are some people so all-consumed by booze and drugs while others can use (even abuse) them without going into a death spiral? I don’t know, but in my experience (anecdotal though this may be), there is an observable risk factor. Anyone who cannot put everything aside for a while and just enjoy “being” is at especial peril. Some, like Cherie, eventually can find their way to this mellow place so that they can stand living without being intoxicated. Cherie Currie is currently a chain saw artist – really.

TV appearance of The Runaways in Japan: the actual group, not a scene from the movie.

Wednesday, April 6, 2011

Higher Learning

Up until several months ago, the California Academy of Sciences home page sported an incredibly simple quiz on elementary science. I don’t know why the quiz was removed, though it’s possible someone in Public Relations decided that making visitors to the site feel like idiots wasn’t in the best interests of the academy. Only 21% of adults answered all of these first three questions correctly.

Question #1

How long does it take for the Earth to go around the Sun?

A. One day

B. One week

C. One month

D. One year

E. Not sure

Question #2

The earliest humans lived at the same time as dinosaurs

A. True

B. False

C. Not sure

Question #3

What percentage of the Earth’s surface is covered by water?

A. 0-25%

B. 26-50%

C. 51-65%

D. 66-75%

E. 76-85%.

F. 86-100%

G. Not sure

The subsequent few questions (which I didn't save anywhere and no longer remember) weren’t any harder, but winnowed the perfect scorers down to 6%. Keep in mind that a solid majority of Americans go on to some higher education beyond high school. So, most quiz-takers were highly (if not particularly well) educated folks. Yet, on the same site, 80% checked the box saying that science education is “essential” for the future of the country and the economy. How would they know?

When I first saw the quiz, I chuckled and then read out loud the first question to an acquaintance who was in the room (and who doesn’t read my blogs). He has a high school diploma and is anything but dense.

“Go around the sun?” he asked.

I answered, “Uh, yes.”

“Oh yeah,” he said. “That’s why the sun rises and sets.”

Jay Leno was nowhere in sight. My response was polite (until now). Actually, fully 47% answered that first question incorrectly. I’m not proposing a solution. As I grow older I am increasingly of the sour opinion that there are no solutions to most human deficiencies, including my own more than ample share of them. Grammar school science is, in fact, taught in grammar school; if most folks choose to forget it all afterward, so be it. I do propose, however, that we remember to laugh whenever a politician (of any stripe) sweet-talks voters in the usual fashion by expressing faith in their intellect. We also should wonder how many of the pols themselves can answer the same questions -- most clearly have trouble with grade school math.

I shouldn’t have to say (and for anyone who has read this far I’m sure I don’t), but the answers to the three above are D-B-D. Among adults who took the quiz, the percentage of correct answers for each of those questions respectively: 53, 59, and 47. 79% missed at least one.

Question #1

How long does it take for the Earth to go around the Sun?

A. One day

B. One week

C. One month

D. One year

E. Not sure

Question #2

The earliest humans lived at the same time as dinosaurs

A. True

B. False

C. Not sure

Question #3

What percentage of the Earth’s surface is covered by water?

A. 0-25%

B. 26-50%

C. 51-65%

D. 66-75%

E. 76-85%.

F. 86-100%

G. Not sure

The subsequent few questions (which I didn't save anywhere and no longer remember) weren’t any harder, but winnowed the perfect scorers down to 6%. Keep in mind that a solid majority of Americans go on to some higher education beyond high school. So, most quiz-takers were highly (if not particularly well) educated folks. Yet, on the same site, 80% checked the box saying that science education is “essential” for the future of the country and the economy. How would they know?

When I first saw the quiz, I chuckled and then read out loud the first question to an acquaintance who was in the room (and who doesn’t read my blogs). He has a high school diploma and is anything but dense.

“Go around the sun?” he asked.

I answered, “Uh, yes.”

“Oh yeah,” he said. “That’s why the sun rises and sets.”

Jay Leno was nowhere in sight. My response was polite (until now). Actually, fully 47% answered that first question incorrectly. I’m not proposing a solution. As I grow older I am increasingly of the sour opinion that there are no solutions to most human deficiencies, including my own more than ample share of them. Grammar school science is, in fact, taught in grammar school; if most folks choose to forget it all afterward, so be it. I do propose, however, that we remember to laugh whenever a politician (of any stripe) sweet-talks voters in the usual fashion by expressing faith in their intellect. We also should wonder how many of the pols themselves can answer the same questions -- most clearly have trouble with grade school math.

I shouldn’t have to say (and for anyone who has read this far I’m sure I don’t), but the answers to the three above are D-B-D. Among adults who took the quiz, the percentage of correct answers for each of those questions respectively: 53, 59, and 47. 79% missed at least one.

Sunday, April 3, 2011

Wheel Appeal

Last night was the first match of the season for Jerzey Derby Brigade Roller Derby!

Roller skating sports, such as races and a version of polo, have been around since the 1880s. From the beginning, these events were rough and tumble. They also were crowd pleasers. Leo Seltzer (1903-1978) saw an unexploited opportunity in them, and in 1935 he invented the team sport of Roller Derby. From the beginning, Roller Derby was mixed gender, with men and women alternating on the track. Seltzer made some tweaks and adjustments over the next few years in light of actual experience, but by 1939 the fundamental rules that still prevail today were in place.

Seltzer scored a hit. Teams sprouted up, and, in the ‘30s and ‘40s, bouts sold out arenas around the country and were broadcast on the radio. It was always a bruising sport, but, after the arrival of television, broadcasters pressured the professional teams to ham up the action visually. For good business reasons they did, but Seltzer never liked this, and he strove to ensure at least the scoring of matches remained honest in order to keep derby a legitimate sport rather than just theater. He obviously succeeded, because derby coaches repeatedly were caught betting with each other on bouts – no insider ever would take the other side of a bet in a fixed bout.

Derby kept a dedicated following, but by the 1970s economics had turned against the professional teams. Other sports won the most lucrative TV contracts, and the costs of transporting the teams to bouts around the country soared. Seltzer said the 70s oil crunch was the final blow. The sport ceased to profitable and the professional leagues shut down.

Derby never went away entirely. Amateur local teams continued to skate, and there were several attempts in the ‘80s and ‘90s to revive the leagues. In 2001 a revival effort finally got real traction with the formation of all-female Roller Derby leagues in Texas that quickly attracted fans. Similar leagues cropped up in other states, and there are now a couple hundred women’s Roller Derby leagues in the US alone, and at least as many more around the world.

One night last year, I whimsically Google-searched for a local team. By “local” I meant somewhere in the northern half of NJ. To my surprise, the nearest team, The Corporal Punishers, skated in Morristown, 7 miles from my door. I attended their next bout which was against the Utica Blue Collar Betties. From the national anthem sung by the Four Old Farts to the post-bout wedding of one of the roller girls in the parking lot outside the rink, the night was enormous fun. The match itself was hard-fought with Morristown ekeing out a victory in the final minutes. I was hooked.

Last night The Corporal Punishers faced a second Morristown team The Major Pains, both of the Jerzey Derby Brigade (http://jerzeyderby.com/), in a sold-out bout. It was the very first bout ever for the newly formed Pains, so, unsurprisingly, the veteran Punishers dominated, the scoreboard reading 203-63 at last glance. For all that, it was hard-fought with the Pains offering some tough blocking that gave even the Punishers’ very effective jammer Assault Shaker (#AK-47) trouble; the Pains’ own jammers including Heinz Catchup (#57) and Maggie Kyllanfall (#187) showed strength and speed. Give them another couple of bouts and the new team will be a co-equal contender.

If the terms jammer and blocker are meaningless to the reader, an instructional video on the rules of the game is below. See you in the stands at the next bout.

Roller skating sports, such as races and a version of polo, have been around since the 1880s. From the beginning, these events were rough and tumble. They also were crowd pleasers. Leo Seltzer (1903-1978) saw an unexploited opportunity in them, and in 1935 he invented the team sport of Roller Derby. From the beginning, Roller Derby was mixed gender, with men and women alternating on the track. Seltzer made some tweaks and adjustments over the next few years in light of actual experience, but by 1939 the fundamental rules that still prevail today were in place.

Seltzer scored a hit. Teams sprouted up, and, in the ‘30s and ‘40s, bouts sold out arenas around the country and were broadcast on the radio. It was always a bruising sport, but, after the arrival of television, broadcasters pressured the professional teams to ham up the action visually. For good business reasons they did, but Seltzer never liked this, and he strove to ensure at least the scoring of matches remained honest in order to keep derby a legitimate sport rather than just theater. He obviously succeeded, because derby coaches repeatedly were caught betting with each other on bouts – no insider ever would take the other side of a bet in a fixed bout.

Derby kept a dedicated following, but by the 1970s economics had turned against the professional teams. Other sports won the most lucrative TV contracts, and the costs of transporting the teams to bouts around the country soared. Seltzer said the 70s oil crunch was the final blow. The sport ceased to profitable and the professional leagues shut down.

Derby never went away entirely. Amateur local teams continued to skate, and there were several attempts in the ‘80s and ‘90s to revive the leagues. In 2001 a revival effort finally got real traction with the formation of all-female Roller Derby leagues in Texas that quickly attracted fans. Similar leagues cropped up in other states, and there are now a couple hundred women’s Roller Derby leagues in the US alone, and at least as many more around the world.

One night last year, I whimsically Google-searched for a local team. By “local” I meant somewhere in the northern half of NJ. To my surprise, the nearest team, The Corporal Punishers, skated in Morristown, 7 miles from my door. I attended their next bout which was against the Utica Blue Collar Betties. From the national anthem sung by the Four Old Farts to the post-bout wedding of one of the roller girls in the parking lot outside the rink, the night was enormous fun. The match itself was hard-fought with Morristown ekeing out a victory in the final minutes. I was hooked.

Last night The Corporal Punishers faced a second Morristown team The Major Pains, both of the Jerzey Derby Brigade (http://jerzeyderby.com/), in a sold-out bout. It was the very first bout ever for the newly formed Pains, so, unsurprisingly, the veteran Punishers dominated, the scoreboard reading 203-63 at last glance. For all that, it was hard-fought with the Pains offering some tough blocking that gave even the Punishers’ very effective jammer Assault Shaker (#AK-47) trouble; the Pains’ own jammers including Heinz Catchup (#57) and Maggie Kyllanfall (#187) showed strength and speed. Give them another couple of bouts and the new team will be a co-equal contender.

If the terms jammer and blocker are meaningless to the reader, an instructional video on the rules of the game is below. See you in the stands at the next bout.

Derby Rules